In the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, salmon are keystone species, supporting wildlife such as birds, bears and otters. The bodies of salmon represent a transfer of nutrients from the ocean, rich in nitrogen, sulfur, carbon and phosphorus, to the forest ecosystem . In the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, salmon are keystone species, supporting wildlife such as birds, bears and otters. The bodies of salmon represent a transfer of nutrients from the ocean, rich in nitrogen, sulfur, carbon and phosphorus, to the forest ecosystem .

All of Alaska's salmon begin their life as a fertilized egg in freshwater. Depending on the species and water temperature, the eggs incubate for a given length of time in the safety of the gravel in a river or lake. Each species of salmon fry will remain in freshwater for a determined length of time.

Some, like sockeye and silver salmon, will stay in freshwater for a year or two. Others, like pink and chum salmon migrate to sea soon after emergence. King (or Chinook) fry typically remain in freshwater for approximately a year.

Adult salmon will remain in the ocean feeding for a given length of time depending on the species. Kings can stay in saltwater for up to 6 years, while pink salmon are on a two-year cycle, meaning they return to spawn in freshwater as two-year-old fish.

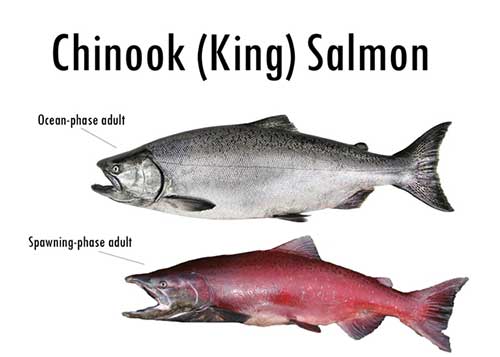

Upon returning to freshwater from the sea, salmon undergo significant physical changes. Some, like sockeye, kings and silvers develop a deep maroon or red coloration. In Southeast Alaska, spawning king salmon are more of a dark brown or blackish color. Chum salmon develop calico bands along each side of their body. Males of each species develop large, hooked jaws, called “kypes.” In addition to developing a kype, male pink and sockeye salmon develop pronounced humps on their back. Consequently, pink salmon are often referred to as “humpys.”

Watching a salmon run is easy, exciting and robustly colorful: The best rivers for viewing these salmon are shallow and clear, so the water appears thick with the fishes’ bright red bodies. The largest salmon ever caught was at the Kenai River. It weighed in at 97.5 pounds. |